Abstract: Life history trait analyses of non-native fishes help identify how novel populations respond to different habitat typologies. Here, using electric fishing and anglers as citizen scientists, scales were collected from the invasive barbel Barbus barbus population from four reaches of the River Severn and Teme, western England. Angler samples were biased towards larger fish, with the smallest fish captured being 410 mm, whereas electric fishing sampled fish down to 60 mm. Scale ageing revealed fish present to over 20 years old in both rivers. Juvenile growth rates were similar across all reaches. Lengths at the last annulus and Linfinity of the von Bertalanffy growth model revealed, however, that fish grew to significantly larger body sizes in a relatively deep and highly impounded reach of the River Severn. Anglers thus supplemented the scale collection and although samples remained limited in number, they provided considerable insights into the spatial demographics of this invasive B. barbus population.

One goal of citizen science is to encourage dissemination of citizen-made observations and knowledge gained about the interactions between the human-made and natural environments—even if that knowledge makes us uncomfortable in confronting potentially damaging cultural traditions. Here we see something as seemingly innocent as a celebratory balloon release can have disastrous consequences. — LFF —

Excerpt: Matthew Bettelheim had seen one too many balloons, deflated and forgotten, lying around in nature. Doing field work in what seemed like remote locations throughout the San Francisco Bay Area, he’d find latex and Mylar balloons, or fragments of them, polluting places where they could pose a threat to wildlife.

They may be beautiful when they soar into the sky, but when they come back to earth, they can be deadly, Bettelheim said. Wildlife can mistake them for food. Once a balloon enters an animal’s digestive system, it can reduce food uptake, block the intestinal tract and cause the animal to slowly starve to death. Wildlife can also become tangled in the balloon material or the pretty ribbons attached to them, making them unable to move or feed, leading to stress, injury, malnutrition and eventually death.

Balloon

Photo credit: © Callum Black, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: TWS member’s citizen science project tracks a wildlife hazard — balloons | THE WILDLIFE SOCIETY

Excerpt: Whale sharks are the largest fish in the world and can grow to more than 40 feet long and more than 65,000 pounds. Despite their massive size, they are harmless “filter feeders” that move slowly through tropical waters, scooping up plankton with gaping mouths. (A)lthough whale sharks are gentle and easy-to-see, they are also constantly on the move, making them difficult for scientists to follow. At the time, this meant only about 1% of tagged whale sharks were ever re-sighted.

“It was a highly inefficient process and impossible to do long term population predictions,” (Jason) Holmberg said. This left scientists with many questions about the species, such as their migration routes and life spans outside captivity, and no one had ever observed them mating or having their young. “Without this information, conservationists could not learn if human activity was impacting whale sharks, or devise strategies to protect them,” Holmberg said.

A better research strategy was needed, and Holmberg thought the pale yellow spots that covered the whale sharks’ bodies could be the key. The spots were configured in unique designs, he noticed, that might be used like fingerprints to distinguish one whale shark from another. These left-side flanks of the whale shark form the “tag” or unique fingerprint of spots used to identify each animal individually. Being an information architect engineer, Holmberg thought that if he could find a way to collect photos of these spot patterns, a computer program could analyze, recognize, and track them.

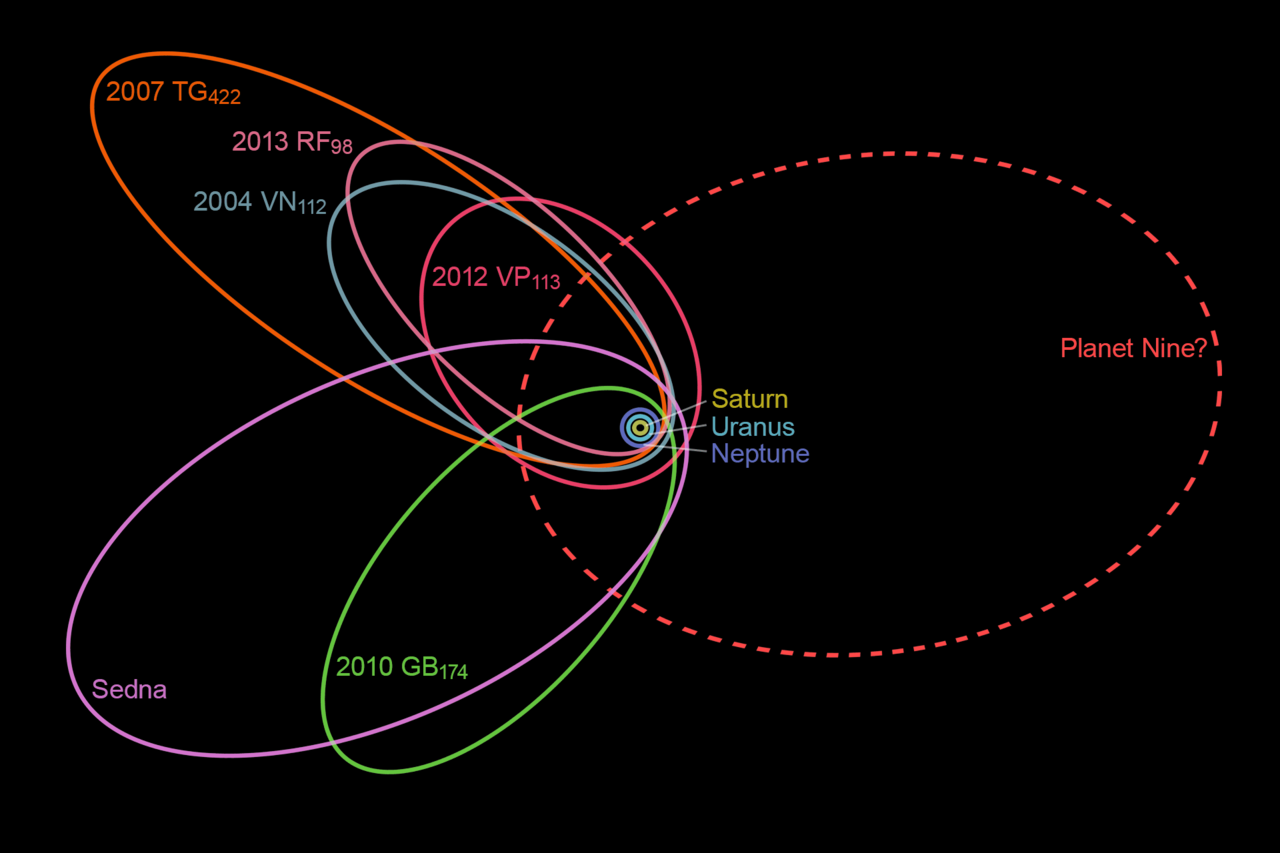

“There’s no plan(et) B” we saw on many of the recent signs on Earth Day marches; however there may be a Planet Nine! Thanks to tens of thousands of citizen scientists who logged four years worth of effort in just three days, there are now four Planet Nine candidates for follow-up. That’s real people-powered research. — LFF —

Excerpt: Citizen scientists have flagged four objects for follow-up study in the hunt for the hypothetical Planet Nine. The four unknown objects were spotted in images of the southern sky captured recently by the SkyMapper telescope at Siding Spring Observatory in Australia. More than 60,000 people from around the world scoured these photos, making about 5 million classifications, said researchers with the Australian National University, which organized the citizen-science project.

The unusually closely spaced orbits of six of the most distant objects in the Kuiper Belt indicate the existence of a ninth planet whose gravity affects these movements.

Image credit: Planet Nine illustration, courtesy Wikimedia Commons, CC0 license

Source: Citizen Scientists Spot Candidates for Planet Nine – Scientific American

Summary:

1.Protected areas are the cornerstone of global conservation, yet financial support for basic monitoring infrastructure is lacking in 60% of them. Citizen science holds potential to address these shortcomings in wildlife monitoring, particularly for resource-limited conservation initiatives in developing countries – if we can account for the reliability of data produced by volunteer citizen scientists (VCS).

2.This study tests the reliability of VCS data vs. data produced by trained ecologists, presenting a hierarchical framework for integrating diverse datasets to assess extra variability from VCS data.

3.Our results show that, while VCS data are likely to be overdispersed for our system, the overdispersion varies widely by species. We contend that citizen science methods, within the context of East African drylands, may be more appropriate for species with large body sizes, which are relatively rare, or those that form small herds. VCS perceptions of the charisma of a species may also influence their enthusiasm for recording it.

4.Tailored program design (such as incentives for VCS) may mitigate the biases in citizen science data and improve overall participation. However, the cost of designing and implementing high quality citizen science programs may be prohibitive for the small protected areas that would most benefit from these approaches.

5.Synthesis and applications. As citizen science methods continue to gain momentum, it is critical that managers remain cautious in their implementation of these programs while working to ensure methods match data purpose. Context-specific tests of citizen science data quality can improve program implementation, and separate data models should be used when volunteer citizen scientists’ variability differs from trained ecologists’ data. Partnerships across protected areas and between protected areas and other conservation institutions could help to cover the costs of citizen science program design and implementation.

Excerpt: For the second year in a row, Oklahoma University (OU) researchers will employ residents from around Oklahoma to collect data for the state’s first major study on amphibian pathogens. The lab, which is run by Cameron Siler, assistant curator of herpetology for the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, is part of the museum. The Oklahoma Infectious Disease Citizen Science Project was initiated in spring 2016 and supplies genetic sample collection kits to the public in order to retrieve more data than lab members can collect alone.

Siler said the citizen science project targets Oklahoma educators to reach a large audience and raise awareness of transferable amphibian diseases. “We’ve kind of developed this study as a way to get additional data from sites that we can’t get to physically ourselves, but also provide a really cool science activity for the teachers,” said Jessa Watters, manager of the Herpetology Collection at the Sam Noble Museum. Kits are sent free of charge to teachers who have access to local ponds or streams, Watters said. Participants are asked to swab the skin of frogs and send them back to the herpetology lab, where lab members will test the swabs for a virulent chytrid fungus, Siler said.

Source: OU research lab encourages aspiring scientists to swab frogs, collect data

Abstract: With around 3,200 tigers (Panthera tigris) left in the wild, the governments of 13 tiger range countries recently declared that there is a need for innovation to aid tiger research and conservation. In response to this call, we created the “Think for Tigers” study to explore whether crowdsourcing has the potential to innovate the way researchers and practitioners monitor tigers in the wild. The study demonstrated that the benefits of crowdsourcing are not restricted only to harnessing the time, labor, and funds from the public but can also be used as a tool to harness creative thinking that can contribute to development of new research tools and approaches. Based on our experience, we make practical recommendations for designing a crowdsourcing initiative as a tool for generating ideas.

The acceptance of citizen science as a valid method for research and participatory monitoring uses rests on the quality of the data produced. Instead of “blaming” citizen participants for providing bad data, this article refreshingly makes it clear that data quality rests on many factors including good project design and training. — LFF —

Abstract: Citizen science has been gaining popularity in ecological research and resource management in general and in urban forestry specifically. As municipalities and nonprofits engage volunteers in tree data collection, it is critical to understand data quality. We investigated observation error by comparing street tree data collected by experts to data collected by less experienced field crews in Lombard, IL; Grand Rapids, MI; Philadelphia, PA; and Malmö, Sweden. Participants occasionally missed trees (1.2%) or counted extra trees (1.0%). Participants were approximately 90% consistent with experts for site type, land use, dieback, and genus identification. Within correct genera, participants recorded species consistent with experts for 84.8% of trees. Mortality status was highly consistent (99.8% of live trees correctly reported as such), however, there were few standing dead trees overall to evaluate this issue. Crown transparency and wood condition had the poorest performance and participants expressed concerns with these variables; we conclude that these variables should be dropped from future citizen science projects. In measuring diameter at breast height (DBH), participants had challenges with multi-stemmed trees. For single-stem trees, DBH measured by participants matched expert values exactly for 20.2% of trees, within 0.254 cm for 54.4%, and within 2.54 cm for 93.3%. Participants’ DBH values were slightly larger than expert DBH on average (+0.33 cm), indicating systematic bias. Volunteer data collection may be a viable option for some urban forest management and research needs, particularly if genus-level identification and DBH at coarse precision are acceptable. To promote greater consistency among field crews, we suggest techniques to encourage consistent population counts, using simpler methods for multi-stemmed trees, providing more resources for species identification, and more photo examples for other variables. Citizen science urban forest inventory and monitoring projects should use data validation and quality assurance procedures to enhance and document data quality.

Photo Credit: Roman et al. 2017, Study site photos appear as Fig. 1 in article.

Source: Data quality in citizen science urban tree inventories

Abstract: Static geosensor networks are comprised of stations with sensor devices providing data relevant for monitoring environmental phenomena in their geographic perimeter. Although early warning systems for disaster management rely on data retrieved from these networks, some limitations exist, largely in terms of insufficient coverage and low density. Crowdsourcing user-generated data is emerging as a working methodology for retrieving real-time data in disaster situations, reducing the aforementioned limitations, and augmenting with real-time data generated voluntarily by nearby citizens. This paper explores the use of crowdsourced user-generated sensor weather data from mobile devices for the creation of a unified and densified geosensor network. Different scenario experiments are adapted, in which weather data are collected using smartphone sensors, integrated with the development of a stabilization algorithm, for determining the user-generated weather data reliability and usability. Showcasing this methodology on a large data volume, a spatiotemporal algorithm was developed for filtering on-line user-generated weather data retrieved from WeatherSignal, and used for simulation and assessment of densifying the static geosensor weather network of Israel. Geostatistical results obtained proved that, although user-generated weather data show small discrepancies when compared to authoritative data, with considerations they can be used alongside authoritative data, producing a densified and augmented weather map that is detailed and continuous.

Abstract: Interest in Citizen Science has grown significantly over the last decade. Much of this interest can be traced to the provision of sophisticated platforms that enable seamless collaboration, cooperation and coordination between professional and amateur scientists. In terms of field research, smart-phones have been widely adopted, automating data collection and enriching observations with photographs, sound recordings and GPS coordinates using embedded sensors hosted on the device itself. Interaction with external sensor platforms such as those normally used in the environmental monitoring domain is practically null-existent. Remedying this deficiency would have positive ramifications for both the professional and citizen science communities. To illustrate the relevant issues, this paper considers a common problem, that of data collection in sparse sensor networks, and proposes a practical solution that would enable citizen scientists act as Human Relays thus facilitating the collection of data from such networks. Broader issues necessary for enabling intelligent sensing using common smart-phones and embedded sensing technologies are then discussed.